The discovery of prehistoric insects preserved in amber offers an extraordinary window into ancient ecosystems, capturing moments frozen in time with unparalleled clarity. These tiny time capsules, formed from the resin of ancient trees, have ensnared creatures in vivid detail, allowing scientists to study behaviors and interactions that would otherwise be lost to the ages. The term "amber prisoners" perfectly encapsulates these entombed organisms, their final acts preserved for millions of years.

One of the most fascinating aspects of these amber-preserved specimens is the behavioral snapshots they provide. Unlike fossils, which often only reveal skeletal structures, amber captures insects mid-movement—feeding, mating, or even struggling to escape. A well-known example is a pair of flies locked in an eternal mating dance, their delicate wings and limbs perfectly intact. Such discoveries challenge previous assumptions about the behaviors of ancient species and provide direct evidence of their daily lives.

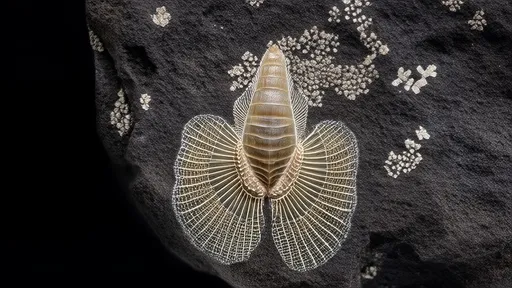

The process of fossilization in amber is nothing short of miraculous. When sticky resin oozed from prehistoric trees, it acted as a natural trap for small creatures. Over millennia, the resin hardened into amber, sealing its captives in an oxygen-free environment that prevented decay. This process preserved not just the insects' physical forms but also minute details like wing patterns, hair, and even the remnants of their last meals. In some cases, air bubbles trapped alongside the insects contain traces of ancient atmospheres, offering clues about Earth's climatic history.

Recent advancements in imaging technology have revolutionized the study of these amber prisoners. High-resolution micro-CT scanning allows researchers to examine specimens in three dimensions without damaging them. This non-invasive technique has revealed intricate anatomical features and even internal structures, such as the digestive tracts of ancient ants or the pollen grains clinging to a beetle's legs. Such findings provide unprecedented insights into the ecological relationships of prehistoric insects and their environments.

Beyond individual specimens, amber deposits also tell broader stories about ancient ecosystems. Certain sites, like the famous Baltic amber forests or the Hukawng Valley in Myanmar, contain a wealth of inclusions that paint a vivid picture of biodiversity millions of years ago. Some amber pieces contain multiple interacting species—parasites attached to hosts, predators caught mid-attack, or insects entangled in spider silk. These interactions suggest complex food webs and ecological dynamics that parallel modern ecosystems in surprising ways.

Perhaps the most haunting aspect of amber-preserved insects is the glimpse they offer into moments of catastrophe. Some specimens appear frozen in desperate struggles—a termite caught in the jaws of an ant, or a wasp immobilized just as it attempted to sting. These snapshots of life and death evoke a sense of immediacy, bridging the vast temporal gap between the prehistoric past and the present. They remind us that, despite the passage of eons, the fundamental struggles for survival remain unchanged.

The study of amber-entombed insects also has implications for modern science. By examining ancient parasites, researchers can trace the evolution of diseases and their vectors. Similarly, studying prehistoric pollinators helps scientists understand the long-term relationship between insects and flowering plants. Some researchers even speculate that preserved DNA fragments, though highly degraded, could one day yield genetic insights into extinct species, though this remains a contentious and technically challenging prospect.

As mining operations and natural erosion continue to unearth new amber deposits, the trove of prehistoric behavioral snapshots grows. Each discovery adds another piece to the puzzle of ancient life, offering fresh perspectives on evolution, extinction, and the intricate web of relationships that has shaped life on Earth. The amber prisoners, silent witnesses to a vanished world, continue to speak volumes about our planet's deep history.

By /Jul 7, 2025

By /Jul 7, 2025

By /Jul 7, 2025

By /Jul 7, 2025

By /Jul 7, 2025

By /Jul 7, 2025

By /Jul 7, 2025

By /Jul 7, 2025

By /Jul 7, 2025

By /Jul 7, 2025

By /Jul 7, 2025

By /Jul 7, 2025

By /Jul 7, 2025

By /Jul 7, 2025

By /Jul 7, 2025

By /Jul 7, 2025

By /Jul 7, 2025

By /Jul 7, 2025