In recent years, a quiet revolution has been taking place in the world of wildlife research. Ordinary citizens, armed with nothing more than smartphones and curiosity, are contributing to scientific discoveries through animal data collection. This phenomenon, known as citizen science, is transforming how researchers gather information about species populations, migration patterns, and behavioral changes.

The concept might seem simple—non-scientists observing and recording animal sightings—but the impact has been profound. Across continents, everyday people are providing researchers with data points that would otherwise require expensive equipment or countless hours in the field. From backyard birdwatchers to urban coyote trackers, these volunteers are creating vast datasets that help scientists understand how wildlife adapts to our changing planet.

What makes citizen science particularly powerful is its scalability. While a single researcher might document a few hundred observations in a season, thousands of participants can generate millions of data points. This massive scale allows scientists to detect patterns that would be invisible in smaller datasets. For instance, subtle shifts in migration timing or changes in species distribution become apparent when observations span entire countries rather than just a few study sites.

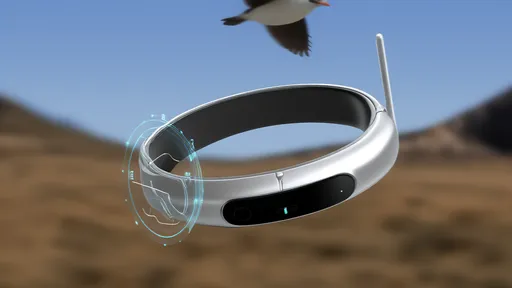

The tools enabling this movement have become increasingly sophisticated. Mobile apps like iNaturalist and eBird have lowered barriers to participation, allowing anyone to upload photos or recordings with precise GPS coordinates. Artificial intelligence helps identify species from these submissions, while verification systems ensure data quality. These platforms don't just collect information—they create communities where novices can learn from experts and where casual observers can become dedicated naturalists.

One remarkable success story comes from the Christmas Bird Count, which began in 1900 as an alternative to holiday bird hunting. Today, this annual event involves over 70,000 participants across the Western Hemisphere, making it the longest-running community science project in history. The data collected has revealed critical insights about how climate change affects bird populations, with some species shifting their winter ranges northward by hundreds of miles.

Marine environments are benefiting from citizen science too. Coral reef monitoring programs train recreational divers to identify fish species and assess reef health. In Australia, the Great Barrier Reef Marine Park Authority incorporates these observations into their management strategies. Similarly, whale watchers contribute to population studies by photographing tail flukes—each as unique as a fingerprint—helping researchers track individual whales across oceans.

Urban areas have become unexpected hotspots for citizen science. As wildlife adapts to city living, residents provide crucial data about these behavioral changes. Projects like Chicago's Urban Wildlife Institute rely on camera traps maintained by local volunteers to study coyotes, raccoons, and other city-dwelling animals. The findings help urban planners create wildlife-friendly spaces and reduce human-animal conflicts.

The educational value of these projects cannot be overstated. Participants often develop deeper connections to nature and stronger conservation ethics. Schools incorporate citizen science into curricula, giving students hands-on experience with the scientific method. For many adults, what begins as a casual hobby evolves into passionate environmental stewardship—they don't just collect data, they become advocates for the species they study.

Of course, challenges exist. Data quality remains a concern, though verification systems and statistical methods have improved significantly. Some scientists initially doubted the reliability of amateur observations, but numerous studies have validated citizen science data when properly structured. The key lies in designing projects with clear protocols, training materials, and quality control measures.

Looking ahead, technology will likely expand citizen science's potential. Camera traps with AI identification, acoustic sensors for bioacoustics monitoring, and even environmental DNA sampling could become tools for public participation. As climate change accelerates, these distributed networks of observers will become increasingly vital for tracking ecological shifts in real time.

Perhaps the most beautiful aspect of citizen science is how it democratizes discovery. A retiree in Florida might document a rare bird species. A schoolchild in Kenya could record pollinator activity that reveals shifting plant-insect relationships. These contributions, small individually but massive collectively, represent a new model for how humanity can understand and protect the natural world—not through isolated experts, but through countless eyes and ears working together.

By /Jul 7, 2025

By /Jul 7, 2025

By /Jul 7, 2025

By /Jul 7, 2025

By /Jul 7, 2025

By /Jul 7, 2025

By /Jul 7, 2025

By /Jul 7, 2025

By /Jul 7, 2025

By /Jul 7, 2025

By /Jul 7, 2025

By /Jul 7, 2025

By /Jul 7, 2025

By /Jul 7, 2025

By /Jul 7, 2025

By /Jul 7, 2025

By /Jul 7, 2025

By /Jul 7, 2025