For decades, popular paleontology has painted entelodonts as the "hell pigs" of prehistoric times – monstrous, carnivorous beasts that terrorized ancient landscapes. This dramatic nickname, coupled with their striking skeletal reconstructions, cemented their reputation as some of the most fearsome mammals to ever walk the Earth. However, emerging research suggests we may have profoundly misunderstood these creatures, whose evolutionary story is far more nuanced than their Hollywood-worthy moniker implies.

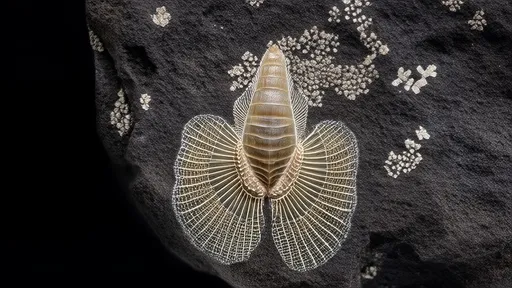

The term "hell pig" itself is a modern fabrication with no scientific basis. Paleontologists never officially classified entelodonts as such; the name emerged from sensationalized documentaries and fossil exhibits capitalizing on their intimidating appearance. Measuring up to six feet tall at the shoulder with massive skulls featuring prominent bony flanges, entelodonts certainly looked the part of prehistoric nightmares. Their teeth – a combination of crushing molars and sharp canines – only added to their fearsome mystique.

Recent isotopic analysis of entelodont bones tells a different story. Chemical signatures preserved in fossilized teeth indicate these animals were likely opportunistic omnivores rather than dedicated predators. Their dental structure, once interpreted as purely meat-shearing, shows clear adaptations for processing tough vegetation. The much-hyped "bone-crushing" jaws may have been used primarily for cracking nuts and breaking down fibrous plant matter – behaviors observed in modern pigs and peccaries.

Behavioral reconstructions are also undergoing revision. The classic depiction of entelodonts as solitary, hyper-aggressive hunters doesn't align with fossil evidence of possible herd behavior. Trackways discovered in Wyoming show multiple individuals moving together, while bonebed sites reveal groups perishing in catastrophic events. Some paleontologists now suggest they may have exhibited complex social structures similar to modern warthogs or forest hogs.

Their ecological role appears more balanced than previously thought. Rather than dominating their environments as apex predators, entelodonts likely filled a generalized niche comparable to bears or wild boars. Fossilized stomach contents and coprolites show varied diets including roots, carrion, small vertebrates, and possibly even shellfish in coastal regions. This dietary flexibility may explain their successful 20-million-year reign across North America and Eurasia.

The bony protrusions on their skulls, once interpreted as weapons for intraspecies combat, might have served multiple purposes. New biomechanical studies propose these structures could have anchored powerful jaw muscles for chewing, supported specialized sensory organs, or even functioned as visual displays – much like the facial wattles of cassowaries. This challenges the long-held assumption that entelodonts were constantly engaged in violent clashes.

Even their extinction narrative requires reassessment. Traditionally blamed for being "outcompeted" by more "advanced" predators like early bears and big cats, evidence now suggests climate change played a greater role. The gradual drying of continental interiors during the Miocene epoch altered vegetation patterns, reducing the mosaic of forests and grasslands that sustained entelodont populations. Their disappearance coincides with broader ecosystem shifts rather than direct competition.

Modern paleontology's shift toward holistic ecosystem analysis reveals how entelodonts fit into their world. Stable isotope mapping shows they occupied transitional zones between forests and open plains, while dental microwear studies confirm seasonal dietary shifts. Far from being monstrous aberrations, they were integral components of Oligocene and Miocene ecosystems, filling niches that no single mammal group occupies today.

The entelodont story exemplifies how first impressions in paleontology can become entrenched. Their initial reconstruction as demonic predators says more about human psychology than prehistoric reality. As one researcher noted, "We tend to project our own fears onto the past, creating monsters where there were just animals trying to survive." This cognitive bias – dubbed "the Jurassic Park effect" – continues to shape popular perceptions of prehistoric life.

Museums are gradually updating their entelodont displays to reflect this new understanding. The Denver Museum of Nature & Science recently replaced its dramatic "battle scene" diorama with an exhibit showing a family group foraging near a watering hole. Such revisions matter because they influence how the public conceptualizes evolution and extinction – not as linear progressions toward "superior" forms, but as complex adaptations to changing environments.

What remains most fascinating about entelodonts isn't their imagined ferocity, but their very real evolutionary success. For perspective, their 20-million-year tenure surpasses the entire existence of hominids to date. Their disappearance represents not failure, but the inevitable turnover that drives biological innovation. In correcting the "hell pig" myth, we gain something more valuable – a nuanced understanding of how diverse life navigates Earth's constant changes.

The next chapter of entelodont research may focus on their soft tissue biology. Recent advances in molecular paleontology could reveal details about their pigmentation, brain structure, or even behavior through preserved proteins. Whatever these future studies uncover, one lesson is already clear: prehistoric creatures deserve to be understood on their own terms, not through the lens of our primal fears or desire for monstrous spectacle.

By /Jul 7, 2025

By /Jul 7, 2025

By /Jul 7, 2025

By /Jul 7, 2025

By /Jul 7, 2025

By /Jul 7, 2025

By /Jul 7, 2025

By /Jul 7, 2025

By /Jul 7, 2025

By /Jul 7, 2025

By /Jul 7, 2025

By /Jul 7, 2025

By /Jul 7, 2025

By /Jul 7, 2025

By /Jul 7, 2025

By /Jul 7, 2025

By /Jul 7, 2025

By /Jul 7, 2025